- Home

- Malavika Kannan

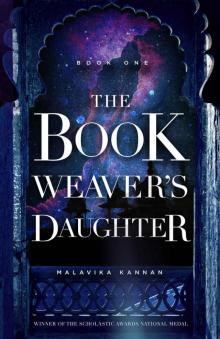

The Bookweaver's Daughter

The Bookweaver's Daughter Read online

THE

BOOK

WEAVER’S

DAUGHTER

Malavika Kannan

Copyright © 2018 Malavika Kannan

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1987741110

ISBN-13: 978-1987741117

DEDICATION

This book is for everyone who felt like their favorite books weren’t woven for them. For all the girls who looked for a heroine in their bathroom mirrors. For a twelve-year-old writer who thought she wasn’t magical. This one’s for you.

CONTENTS

Prologue

1

Chapter One

3

Chapter Two

19

Chapter Three

31

Chapter Four

44

Chapter Five

55

Chapter Six

64

Chapter Seven

75

Chapter Eight

81

Chapter Nine

88

Chapter Ten

103

Chapter Eleven

122

CONTENTS

Chapter Twelve

138

Chapter Thirteen

149

Chapter Fourteen

163

Chapter Fifteen

180

Chapter Sixteen

198

Chapter Seventeen

208

Chapter Eighteen

225

Chapter Nineteen

237

Chapter Twenty

250

Chapter Twenty-One

272

Epilogue

278

If the radiance of a thousand suns burst at once into the sky,

That would be like the splendor of the Mighty One.

I would become Death, the Shatterer of Worlds.

The Bhagavad Gita

PrOLOGUE

The problem with weaving stories is that you can never quite know when yours will begin.

I didn’t.

What I did know was that the magic had always been a part of me, potent as burned stars and night-colored dreams. And so was danger, following the magic like a filly following a mare. In a kingdom where legacies were at war, these were the only two things I was certain of.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The Bookweaver named me after the reya flowers that bloom in Kasmira in the spring: luminous and silver, like shards of broken pearl. “Reya Kandhari,” he once told me. “A powerful name for a powerful girl.”

I sometimes think that it’s the sight of rippling silver reya fields that first inspired me to write. I wanted to capture all of that beauty and enigma and save it from the darkness.

Once upon a time, my father dreamed of placing the traditional wreath of reya on my brow and passing his gift down to me. But that dream had been ripped apart years ago, tearing with it a girl with a legacy for a last name, and leaving an unfinished tale in her place.

Now all I have are the words and the pressing, bone-deep cold.

chapter one

The Bookweaver once told me that when we die, we all leave something behind.

A cobbler leaves behind a legacy of warmly clad feet; a baker leaves behind memories of sated stomachs; a writer leaves behind a testament to our humanity. You can leave behind a book or a house or a child. Really, it can be anything, as long as it was once warm from your touch and alight with your fire and carries a piece of you within it forever.

The problem is, he said, we don’t realize the gravity of our duty until we’re forced to act. All of a sudden, we find ourselves unanchored, and that’s when we realize that we forgot to leave behind our mark. And by then, there’s no turning back.

“Reya Patel!”

The sound of my name jarred me back to reality. I looked down from my tree branch to see Lord Gilani, the overlord of the Fields, glaring at me.

“Are you expecting the mangoes to harvest themselves, Patel?”

I took a deep breath.

“No,” I said. “I’m almost done.”

Gilani rolled his eyes. “I need another half-bushel before sundown. Get to work.”

I envisioned the mango tree toppling down on him as I slung my basket over my shoulder and started to climb.

A strong branch, laden with mangoes, loomed over my head as if taunting me. I wrestled its fruit into the basket with vengeance. And then I continued to climb, because in moments like this, it felt easier to leave my anger on the ground.

From the top of the tree, I could see the Fields unfolded before me: the orchards, the pastures, and other peasants toiling in the heat. Beyond that sprawled the entire Raj— raucous bazaars, clay gardens, and homes painted brightly to ward off demons. Pearl-cleaved minarets that challenged the heavens themselves. And most hauntingly, the royal mahal, reflected a thousand times by rivers that unspooled like silk.

Once the basket was full, I tied it to a pulley and lowered it the ground. As the basket descended, I remembered what my father had once told me about the cosmic laws of karma. I wondered what I’d done to get mine so out of balance, and how long I had to wait until the universe repaid its debt.

Down below, a gray-eyed girl hefted the basket onto her shoulder and squinted up at me.

“Reya?” she called.

Nina’s voice was even enough, but her eyes kept darting up to the sky, where storm clouds were gathering. A cold wind washed over the Fields, sending crops rippling. The storm was going to be especially bad today—I could see it in the restless pacing of the overlords, the hushed whispers, and the darkness billowing and descending upon us.

Somehow—and perhaps I was imagining it, but I picked up on the stench of decay, laced within the drowsy scent of mangoes. I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was stirring—a story waiting to unfold, a legend in the making.

“You look depressed,” Nina continued matter-of-factly. “You promised me that the angsty phase was over.”

She smiled at me. For a moment, it felt like we were still eight years old, and it was my first day of mandatory service in the Fields. I had just scraped my knee on a branch, and she had reached for me with that same smile. I knew right then that when she took my hand, she was also taking a piece of my heart. Because in spite of the secrets I kept from her, there was something about Nina Nadeer that made me certain that scraped knees could be healed, rain storms could be weathered, and humans could leave their mark.

“You worry too much about me,” I called down, resisting the urge to check the sky again. “I’ll be fine.”

Her eyes crinkled a little, like she didn’t quite believe me.

“I’ve been meaning to tell you,” she said. “There’s a rumor that there’s going to be a raid on the Fringes soon, so be careful going home tonight. King Jahan’s on a witch hunt for rebels.”

I ignored the jolt of anger in my stomach.

“Forcing us all to work the Fields isn’t enough for him?” I said. “The Zakirs drove out the Mages seven years ago. There’s literally nobody left to rebel.”

“They’re getting paranoid,” said Nina sagely, stooping back over the mangoes. “I don’t blame them. These are dangerous times.”

I opened my mouth to respond, and that’s when I felt it.

Heat seared the skin between my collarbones, so fleeting and powerful that I nearly fell off the branch. I rolled completely sideways, one hand clutching the fork of the tree, the other reaching for the pearl I wore on my neck.

Someone screamed as the branch tipped precariously, sliding out of my grip. I flailed, fingers scrabbling on the decaying bark—it was

smooth, entirely too smooth—and even as the blood rushed into my head, all I could hear was the screaming. I wished it would stop.

Right before the branch broke, I realized that the screams were mine.

There was an awful crack, and for a moment, I was suspended in midair—there was nothing but iron-colored clouds, a clean blank page—then the ground rushed up at me all at once as I tumbled down, broken branch and all, landing flat on my back.

“Ni—Nina—” I couldn’t get the words out. My throat had closed up: whether from the burning pearl or restrained tears, I wasn’t sure.

“Reya!” Nina dropped her basket and pulled me up to my feet. Vaguely, I heard her fuss over me, but I couldn’t focus on that—all I could think about was the panic, clawing its way up my throat.

I hadn’t imagined it: the pearl had burned. And that could only mean one thing. The Bookweaver was in danger.

My pearl was an illegal amulet, and its lifeblood was connected to my father’s. If anyone found out about it, I could be accused of being a Mage. I’d never understood how the pearl worked, but its meaning was devastating: if it burned, my father’s life was in danger. If I was too late, it would shatter.

I could feel the pearl throbbing against my heartbeat. I had to get home to him.

A clap of thunder rumbled through the clouds, and the skies split at last, releasing a horrible fury on the peasants below. I stumbled forward, and Nina stretched out her hand.

The thunder sounded like a thousand pearls spilled by a careless hand, the beating tabla drums for a riot of rain and wind. It was so crowded that I could barely see where I was going: only Nina’s hand guided me through the stampede. Despite her comforting presence, my panic was rising.

I slipped my hand out of Nina’s, but she held on tight. “Don’t lose me,” she said, shouting to be heard over the wind. “I know where we can find shelter—”

“Let go,” I said, tugging against her grip. She whirled around, confused. “But you’ll get trampled—”

“Be careful,” I managed, and then I wrenched my hand free from Nina’s. She reached for me, frantic, but the chaos swept her away, drowning her shouts beneath an army of thundering feet.

I’m sorry, I wanted to shout. But I didn’t. She wouldn’t have heard me, anyways.

I cut through the orchards, pulling my hood up as I ran. Herding as one against the staggering winds, nobody noticed a lone girl escaping into the forbidden outskirts of the Fields.

There it stood: the Fields wall. It kept hungry animals out—and hungry peasants in. Almost anyone would assume that the wall was impassable. But I’m not one of those people, and neither was my mother. When I was younger, she used to remind me, “There’s always a way out if you’re persistent enough to find it.”

She was right. After weeks of scoping, I had found the chink in the armor: a single loose stone. It took a few blows from a shovel before the stone gave way. For seven years, it had remained my only means of escape.

I gave a sharp push, and the stone slid out, revealing a narrow opening. Through the gap, I caught a glimpse of the rain-soaked streets of the Raj.

Before I slipped through the gap, I looked back at the Fields: at the flat blankets of red-packed earth, the bowed orchards of mango trees, and—maybe I was just imagining it—a pair of forlorn gray eyes. And then I was gone.

Kasmira’s crooked streets, normally teeming with peddlers, cowherds, and wandering minstrels, were abandoned. The colorful rangoli that usually adorned doorsteps had been washed away, leaving blood-colored stains on the footpaths. Only the royal mahal, dark and foreboding in the distance, stood firm beyond the lashing rain.

I caught a glimpse of myself in a darkened window as I ran, and my expression startled me. Beneath the hood of my cloak, my green eyes were unrecognizable. They didn’t look scared. They looked wild.

The sky was filmy and dark by the time I reached our home—a crumbling workshop in the edge of the Fringes. Even after seven years, the cottage carried scars of battle: burn marks on the walls, sword gouges in the streets. To some of Kasmira’s most oppressed, these marks represented resistance from the time Jahan Zakir first took over.

To me, they served as a warning: we could hide, but we could never truly escape the king.

I knocked on our door, proclaimed by a hand-painted sign to be a bookbinder’s workshop.

“Father?”

There was no answer.

I pounded again. “It’s me. You can open up.”

Silence.

My stomach turned, and in spite of myself, my fingers were trembling as I fumbled for my key. “I’m coming in—”

I swung open the door, and the firelight engulfed me all at once.

My father was curled like a cat in the corner, hidden behind mountains of green hide and vellum. Wax lamps dripped freely onto his desk, but he didn’t seem to notice. He was writing with an almost religious fervor, oblivious to the rest of the world—including his daughter behind the door.

Relief made my hands shake, and I slipped them into my pockets to hide their tremor.

“I’m home,” I said at last, because I didn’t know what else to say.

Amar Kandhari squinted up to the doorway and noticed me at last. He beckoned me inside. “Reya,” he murmured. “You’re early.”

He caught sight of my expression and frowned. “Your hands are shaking in your pockets.”

I forced a smile. “You weren’t feeling well today, and Nina warned me about a raid in the Fringes,” I said. “I guess I got scared.”

“The pearl didn’t burn, did it?” he said, looking concerned.

There was something about the way he spoke that made me feel like he was a mythical being, like he somehow didn’t exist. Because although he was disguised as a lowly bookbinder, Amar Kandhari was the Bookweaver, Kasmira’s patron of literature. He was one of the three Yogis, the ancient guardians of Kasmira. He was also my father.

“No,” I lied. “Nothing like that. But it’s good to see you writing again.” I touched his feet briefly before rising to check his temperature.

“Your forehead is scalding. Why didn’t you take anything for it?”

The Bookweaver smiled weakly, but his eyes didn’t quite meet mine. “It’s just a fever,” he said. “I’ve been burning up all day. But it’s nothing for you to worry about.”

I exhaled slowly. He was getting weaker with each illness. I rarely allowed myself to think about it, but I was always afraid he wouldn’t pull through again.

“Did you drink the rasam?” I asked, crouching beside the fire for warmth.

My father frowned, and I realized that the rasam I’d made for him this morning lay untouched in its pot. “Honestly, Reya, I haven’t felt hungry for hours.”

I bit my lip. If he couldn’t even bring himself to eat, then the illness was worse than I’d feared.

“It doesn’t matter,” I said, sounding much more confident than I felt. “You’ve got to keep up your strength. That’s the only way you can fight this thing.”

He watched me silently as I heated the rasam in the pot. His expression was unreadable—I wondered if he suspected that things were far worse than I was letting on.

The aroma of warm spices began to permeate the shop. I was grateful for the cheerily bubbling pot and roaring rain for filling the guilty silence between us.

“I promise it’ll taste better hot,” I said, passing him a steaming bowl. “It’s not as good as Mom’s, but still—”

His reproachful eyes met mine, and I stopped mid-sentence.

I had forgotten how fragile he could be on days like this. Huddled behind his bookbinding supplies, it wasn’t hard to pretend that the Bookweaver was a child himself. Only his eyes, deep-set and haunted, belied his actual age.

The roof creaked in protest against the drumming rain, drowning out the hissing pot and my father’s labored breaths. The rasam seemed to be working: his eyes, previously glassy, now shone like compressed firelight. He s

et the bowl aside and looked me in the face for the first time that day.

“Reya,” he started, and the pain in his voice was palpable, like bruises beneath skin. “I’m sorry.”

The Bookweaver's Daughter

The Bookweaver's Daughter